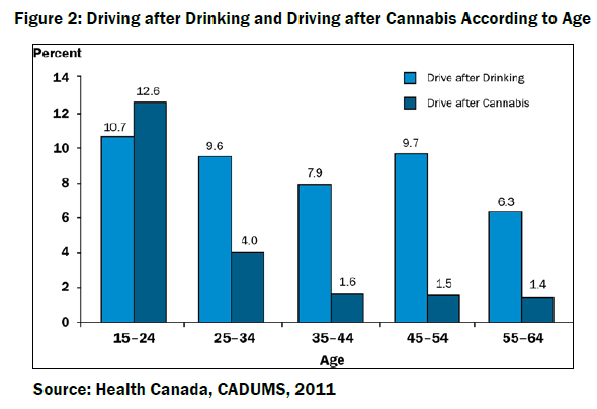

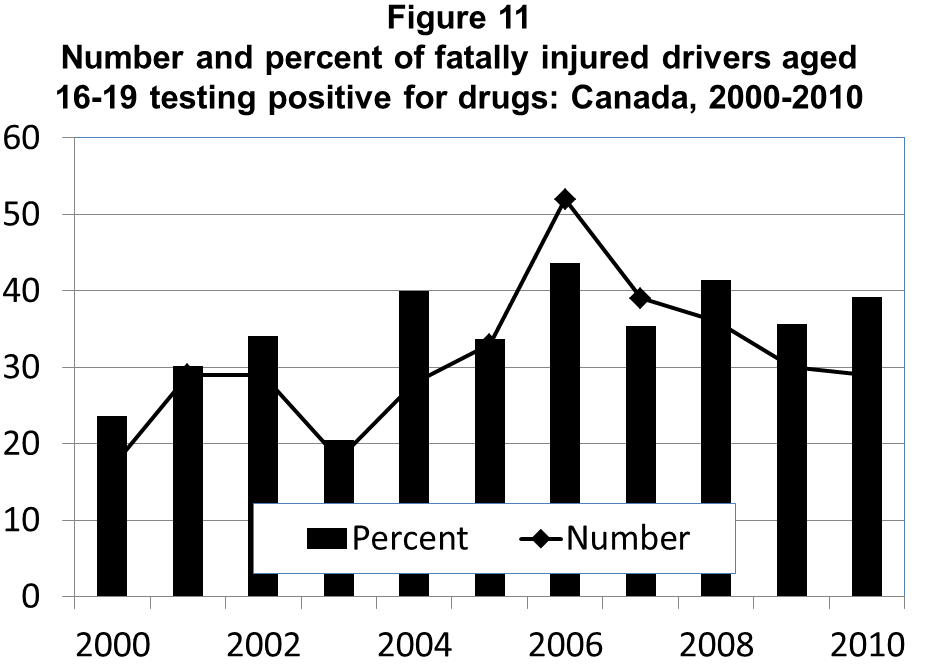

The Issues - Drug ImpairmentWHAT IS... What is drugged driving? BEHAVIOURS What is the most common drug found in young drivers? ATTITUDES, CONCERNS AND PERCEPTIONS Are Canadians concerned about the problem of youth and drugged driving? Are there Federal drugged driving laws? What is being done on the roads in order to apprehend drugged drivers? WHAT IS... The Canadian Center on Substance Abuse defines the terms “drugged driving” and “drug-impaired driving” as driving a motor vehicle while impaired by any type of drug or medication or combination of drugs, medication and alcohol. These include illegal substances, mind-altering prescription medications, and over-the-counter remedies and medications that affect an individual’s ability to drive safely.1 How common is drugged driving? The drugged driving problem is becoming comparable to the drunk-driving problem, and needs to be addressed with as much urgency. Results of alcohol and drug tests performed on drivers who died in motor vehicle crashes in 2008 in Canada reveal that 37% were positive for drugs compared to 41% that tested positive for alcohol.2 Similarly, a 2010 roadside survey in British Columbia of 2,840 randomly selected vehicles found that 7% of drivers tested positive for drugs and 10% had alcohol in their system.3 Both studies found only 4% more drivers driving drunk compared to drugged, meaning that drugged driving is almost as common as drunk driving. This trend is seen among young drivers as well. A Canadian survey in 2011 of high school students showed that 21% had driven at least once within an hour of using drugs. When asked if the students had been a passenger in a vehicle where the driver had used drugs 50% answered yes.4 In Ontario, a 2009 study of students found that 17% of drivers in grades 10-12 reported driving a vehicle within one hour of using cannabis.5 Drivers testing positive for cannabis is highest for those under 19 followed by those aged 19-24.6

1 Weekes 2005 BEHAVIOURS What is the most common drug found in young drivers? Cannabis (also known as marijuana or weed), which is illegal, is the most common drug used by youth.8 Results from the 2009 Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Survey indicated that 33% of Canadians aged 15-24 had used cannabis at least once in the past year. It is also the drug most often found in drivers who are fatally injured in a crash.9 Cannabis causes euphoria, slowed thinking, confusion, impaired memory and learning, increased heart rate and anxiety. These effects are felt within minutes, peak after about half an hour and can last up to two hours.10 The effects of cannabis on driving and the effects of cannabis in combination with alcohol are discussed in further sections. Cannabis is accessible and convenient. It is easier to hide than alcohol (smaller in size), and teens feel it is less likely to be detected by their parents. It is quicker to get high from cannabis than to get drunk from alcohol and cannabis is often more accessible than alcohol. For example, stores that sell alcohol require I.D. but drug dealers will sell to any one who is buying regardless of age. Youth also feel it is less likely they will get arrested for driving high because it cannot be detected by a breathalyser.11 These factors combine to make cannabis the most popular drug and the most likely drug to be in the body of young drivers while driving. What other drugs are available to young drivers? There are three categories of drugs used by youth: illegal drugs, prescription drugs and over the counter drugs.

The effects of drugs on each individual are unique, and depend on the dosage, how recently they have been taken and their body chemistry. For instance, some one who has been taking a prescription drug for many months may have developed a tolerance compared to those who are taking the drug for the first time. Age also affects how the brain reacts to drugs; the younger the user the more damage that may occur. For instance, teens aged 12 to 17 who smoke marijuana weekly are three times more likely to have thoughts of suicide than non-users.15 Drug effects are much more dangerous in combination with each other and with alcohol. (More information about brain development of young drivers available here) Cannabis significantly affects the skills necessary for driving. It causes slowed thinking, which delays reaction time to important events occurring on the road and distorts time and distance perception, making it difficult for the driver to navigate turns into oncoming traffic. Concentration and attention span are also decreased, increasing the likelihood that the driver will be distracted from watching the road. The crash rate of cannabis users can be anywhere from two to six times higher than sober drivers, depending on duration and quantity of the drug.16 Cocaine, the most common illegal drug found in fatally injured drivers next to cannabis, is associated with speeding, losing control of the vehicle, making unsafe turns in front of other vehicles, aggressive driving and inattentive driving.17Those driving under the influence of cocaine are two to ten times more likely to crash.18 The prescription drug benzodiazepine (such as Xanax, Valium, Ativan) is the most common psychoactive medicine found in North American and European drivers.19 This drug affects hand-eye coordination, making it difficult for the driver to perform the physical functions of driving (steering, shifting gears) and impairs divided attention, a skill needed to successfully handle the many demands of driving. Similar to cannabis, it lengthens reaction time and can cause confusion and sedation. For users who are new to using the drug, crash risk is two to five times higher than a sober driver.20 What type of driver is more likely to drive drugged? Drivers who are young and male are most likely to drive drugged.21 Out of all age groups, 15-25 year olds are the most likely to use drugs,22 making drugged driving a big issue for young drivers. The more frequently a youth uses drugs, the more likely they will drive after doing drugs or get in a vehicle with an impaired driver.23 The attitude of a young driver also plays a role in their drugged driving behaviour. A study conducted which focused on adolescent behaviour found that those who drive risky simply because it is ‘fun’ are more likely to use cannabis, drink and are sexually experienced.24 Therefore, the personality type of a young driver might increase their likelihood of driving while on drugs; those with an ‘overall risk-taking’ attitude are more willing to do drugs and are likely more willing to drive while high. How many young drivers are fatally injured while driving drugged in Canada?

8 ECMT 2006 ATTITUDES, CONCERNS AND PERCEPTIONS Are Canadians concerned about the problem of youth and drugged driving? Yes. In a 2010 Road Safety Monitor (RSM) survey conducted by the Traffic Injury Research Foundation (TIRF), 83% of adult Canadians viewed young drivers impaired by drugs as a very serious or extremely serious problem. Similarly, 85% of respondents judged the issue of young drivers being impaired by alcohol to be a very serious or extremely serious problem.26 This means that adults consider the dangers of drugged driving to be comparable to the dangers of drunk driving for young drivers. In the same RSM, 84% of adult respondents agreed that they could not drive home safely after taking illegal drugs and 86% said the same about driving home safely after drinking alcohol. This shows that Canadian adults consider both driving under the influence of drugs and driving under the influence of alcohol as dangerous actions. Are young drivers concerned about the problem of drugged driving? The 2003 RSM found that respondents under the age of 30 were the least likely age group to perceive driving while under the influence of drugs as a problem.27 In the 2010 RSM 86% of young drivers agreed they could not drive home safely after drinking alcohol but only 70% felt the same about taking illegal drugs and driving home.28 In a 2011 survey, Australian college students expressed the belief that driving while on certain drugs is safer than driving while drunk. Some students believed illegal drugs improved their driving (e.g., ‘Speed’ made them more alert) and most considered being high from cannabis as the ‘safest way’ to drive under the influence.29 A recent Canadian public opinion survey also found that youth are concerned about the drugged driving problem.30 However, it was determined that even though drug-impaired driving is a concern among youth, they represent the age group who are least concerned about the issue. Generally speaking, respondents aged 35 and older are more concerned about drugged driving, whether they are illicit or medicinal, compared to younger drivers. How often are impaired drivers both drunk and drugged? There is a very good chance that drivers found with some type of drug in their system will also have alcohol in their system. For instance, a study conducted in Quebec on fatally injured drivers discovered that out of those who tested positive for drugs 40% also had alcohol in their system.31 An Ontario study found an even higher amount of fatally injured drivers with both substances: among those who tested positive for cannabis, 84% were also positive for alcohol.32 The effects of combining drugs and alcohol can be quite dangerous. For instance, mixing cannabis and alcohol will cause both immediate impairment (cannabis is fast acting and strongest at the onset) and long-lasting impairment (alcohol’s effects maximize later and do not decrease as quickly as cannabis). Together, the substances interact to produce greater fatigue and hangover effect than taking either of the two alone.33 As well, a study conducted in the Netherlands found that driving after combining drugs and alcohol increased crash risk ten times more than driving on drugs alone.34 26 Marcoux et al. 2011 LEGISLATION Are there Federal drugged driving laws? Yes. The Federal Criminal Code of Canada (CCC) contains a law that makes it illegal to operate a vehicle while impaired by alcohol or a drug, or a combination of both.35 In 2008, The Tackling Violent Crime Act was passed which allows police officers, who reasonably suspect that a person who is operating a vehicle is under the influence of alcohol or drugs, to demand that the driver participate in Standardized Field Sobriety Test (SFSTs). If these tests prove the driver is impaired by drugs a Drug Recognition Expert (DRE) is called in to perform a more thorough examination, that includes taking a bodily fluid sample.36 If a driver is caught under the influence of drugs they face the same penalties as those caught under the influence of alcohol. If they refuse to provide a SFST or a bodily fluid sample they are charged with a criminal offence. Penalties for the offence include:

Are there provincial/ territorial drugged driving laws? Yes. In British Columbia, Manitoba, Alberta, Saskatchewan, the Northwest Territories and the Yukon a driver’s licence is suspended for 24 hours if an assessment by a police officer proves that the driver’s ability to drive is affected by the influence of drugs.37 In Ontario, a 90 day licence suspension is given to drivers who refuse to take a SFST, provide a fluid sample or submit to a DRE’s testing.38 In Newfoundland, if an officer observes driver behaviour that is considered drug- related, a seven day licence suspension is given. How do young Canadians perceive measures to prevent drug-impaired driving? 35 Department of Justice Canada 2012 SOLUTIONS What is being done on the roads in order to apprehend drugged drivers? Detecting drugs in a driver’s system is not as simple as detecting alcohol in a driver’s system but it is possible for police to detect the presence of drugs. There are several drugs that could influence a driver and detection of these various drugs is not accomplished using a breathalyser. Instead, more intrusive tests are needed, such as collecting blood, urine, or saliva samples. Saliva collection is the least intrusive and swabs have been developed for easier roadside drug detection. This technology is already being used by some countries (such as Australia) and would benefit the Canadian roadside drug test. Presently, Canadian roadside drug tests involve physical coordination tests (touching finger to nose, walking and turning) and bodily inspection (checking pulse, measuring pupil size, testing eye movement) to determine if the driver is under the influence of drugs. What campaigns and programs are working to reduce drugged driving? Many impaired driving campaigns focus on alcohol but as concern about drugged driving grows, it is being incorporated into already existing drunk driving campaigns. There have been legislative changes that address drugged driving (such as the 24 hour licence suspensions and the roadside drug tests) and remedial programs, delivered in each province, that are beginning to address both alcohol and drug problems for drivers who have been convicted of impaired driving. Creating public awareness about drugged driving would help decrease its prevalence. The P.A.R.T.Y Program (Prevent Alcohol and Risk-Related Trauma in Youth) addresses all issues related to taking unsafe risks as teens. This program highlights what can happen after a terrible crash and brings to light the reality of being paralyzed or dead and the consequences for the family and friends of drivers. It emphasizes that driving under the influence of alcohol, drugs or both can lead to these consequences. Studies have shown that the P.A.R.T.Y Program effectively reduces driving-related trauma injuries among program participants.40 Information on P.A.R.T.Y. Program can be found at: http://partyprogram.com/home.aspx The “Pot and Driving Campaign” focuses specifically on drugged driving. Cannabis is known as the most popular drug used by young Canadians making it the most important drug to highlight to youth. This campaign focuses on eliminating the misconception that cannabis does not have negative effects on driving and stresses that it should be considered as dangerous as alcohol when getting behind the wheel. What alternatives to drugged driving and riding with a drugged driver are available to young drivers? There are other options available instead of getting behind a wheel while on drugs. A social night out should begin with a game plan such as:

Most importantly, watch out for friends or loved ones when you know they have done drugs. Don’t let them drive and refuse to be a passenger in their car. Asbridge, M., Poulin, C., Donato, A. (2005). Motor vehicle collision risk and driving under the influence of cannabis: Evidence from adolescents in Atlantic Canada. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 37(6): 1025-1034. Banfield, J.M, Gomez, M., Kiss, A. (2011). Effectiveness of the P.A.R.T.Y (Prevent Alcohol and Risk-Related Trauma in Youth) Program in Preventing Traumatic Injuries: A 10-Year Analysis. Journal of Trauma, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 70(3): 732-735. Barrie, L.R., Jones, S.C., Wiese, E. (2011). “At least I’m not drink-driving”: Formative research for a social marketing campaign to reduce drug-driving among young drivers. Australasian Marketing Journal. 19: 71-75. Beasley, E.E., Beirness, D.J., Porath-Waller, A.J., 2011. A Comparison of Drug and Alcohol-involved Motor Vehicle Driver Fatalities. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Beirness, D.J. (2012). The Official Newsletter of the Canadian Association of Road Safety Professionals. Impaired Driving. The Safety Network. Beirness, D. J., Beasley, E. E. (2011). Alcohol and Drug Use Among Drivers: British Columbia Roadside Survey 2010. Canadian Center on Substance Abuse. Ottawa, Canada. Beirness, D. J., Simpson, H. M., Desmond, K. (2003). The Road Safety Monitor 2002: Drugs and Driving. Traffic Injury Research Foundation. Ottawa, Ontario. Beirness, D.J., Simpson, H.M., Williams, A.F. (2006). Role of Cannabis and Benzodiazepines in Motor Vehicle Crashes. Drugs and Traffic: A Symposium. June 2005. Transportation Research Circular. Woods Hole, United States. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (CCSA). (2011). Cross Canada Report on Student Alcohol and Drug Use. Technical Report. Student Drug Use Surveys Working Group. Ottawa, Canada. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (CCSA). (2011). Cross Canada Report on Student Alcohol and Drug Use. Technical Report. Student Drug Use Surveys Working Group. Ottawa, Canada. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). (2009). Info on Prescription Opioids. Perscription Opioids Services. Retrieved from: http://www.camh.net/About_ Addiction_ Mental_Health/AMH101/info_pr_opioids.html. Department of Justice Canada. (2012). The Criminal Code of Canada. Retrieve from: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/page-118.html#docCont. Driving Under the Influence of Drugs, alcohol and medicines (DRUID). (2012). Summary of Main Druid Results. DRUID Conference. Washington DC, United States. European Conference of Ministers of Transport (ECMT). (2006). Young Drivers: The Road to Safety. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Paris, France. Government of British Columbia. (2012). 215: 24 Hour Prohibition. Motor Vehicle Act. Retrieved from: http://www.bclaws.ca/EPLibrari es/bclaws_new /document/LOC/fre eside/--%20M%20--/Motor%20Vehicle %20Act%20RSBC%201 996%20c.%20318/00 _Act/96318_00.htm. Government of Saskatchewan. (2012). T-18.1- The Traffic Safety Act. Publications Center Saskatchewan Documents. Retrieved from: http://www.qp.gov.sk.ca/documents /english/Statutes/Statutes/T18-1.pdf. Government of Alberta. (2011). Traffic Safety Act. Alberta Queen’s Printer. Retrieved from: http://www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/t06.pdf. Government of Ontario (1990). Highway Traffic Act. Service Ontario E-Laws. Retrieved From: http://www.search.e-laws.gov.on.ca/en/isysquery/869fa199-c621-4d65-849a-0f2a96b6beb5/1/doc/?search=browseStatutes&context=#hit1. Greenblatt, J. (1998). Adolescent self-reported behaviors and their association with marijuana use. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, 1994-1996.The Substance Abuse Mental Health Service Administration. Hanson, D.J. (2011). Drugged Driving Safer than Drunk Driving? Alcohol Problems and Solutions. Retrieved from: http://www2.potsdam.edu/hansondj /DrivingIssues/11044320 32.html Jessor, R. (1987). Risky Driving and Adolescent Problem Behaviour: An Extension of Problem Behaviour Theory. Alcohol, Drugs and Driving. 3(3/4): 1-11. Jonah, B. (2013). CCMTA Public Opinion Survey of Drugs and Driving in Canada: Summary Report. Canadian Council of Motor Transportation Administrators (CCMTA). Marcoux, K., Robertson, R., Vanlaar, W. (2011). Road Safety Monitor 2010: Youth Drinking and Driving. Traffic Injury Research Foundation. Ottawa, Canada. Paglia-Boak, A., Mann, R.E., Adlaf, E.M., Rehm, J. (2009). OSDUHS Highlights: Drug Use Among Ontario Students 1977-2009. Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Toronto, Ontario. Peck, R.C., Biasotti, A., Boland, P.N., Mallory, C., Reeve, V. (1986). The Effects of Marijuana and Alcohol on Actual Driving Performance. Alcohol, Drugs and Driving. 2(3/4): 135-154. Porath-Waller, A. J., Fried, P.A. (2007). Adolescent Marijuana- and Alcohol-Impaired Driving Behaviors. International Council on Alcohol, Drugs and Traffic Safety. Seattle, Washington. Shinar, D. (2006). Drug Effects and Their Significance for Traffic Safety. Drugs and Traffic: A Symposium. June 2005. Transportation Research Circular. Woods Hole, United States. Simpson, H., Singhal, D., Vanlaar, W., Mayhew, D. (2006). The Road Safety Monitor: Drugs and Driving. Traffic Injury Research Foundation. Ottawa, Canada. Stewart, K. (2006). Overview and Summary. Drugs and Traffic: A Symposium. June 2005. Transportation Research Circular. Woods Hole, United States. Weekes, J. (2005). Drugs and Driving FAQs. Canadian Center on Substance Abuse (CCSA). Ottawa, Canada. Wood, W. (2010). Interactions Between Psychiatric Medications and Substances of Abuse. Provincial 2010 Summer Institute. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Toronto, Canada. Yost, G. (2011). Canada’s Drug Drug-impaired Driving Legislation. International Drugs and Driving Symposium. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Montreal, Canada. Last updated February 2014 |

|